The core team behind the success. Pentti Palmroth with his sons Pertti and Juhani in the 1950s.

From the manor’s son to a shoemaker

Pentti Johannes, the oldest son of the owners of the Partola Manor, Hilma and Hannes Palmroth, has told that he was actually supposed to become a diplomat, but chance lead him to the shoe industry. After secondary school and commercial college, he stayed in Germany mainly to learn the language, and he was offered work as the secretary at the consulate; a position which was to open in a year. He promised to get back on the offer, worked in a German shoe factory while he waited for the secretarial position, and then announced that he would pursue a profession in shoemaking after all. After making the decision, he worked in a shoe factory in Tampere in all its departments, and then in shoe factories around the United States. In America, he also completed an 18-month course in a school of economics. After returning to Finland, Pentti Palmroth worked as the technical assistant manager at the Aaltonen shoe factory for three years, and then as the technical director at the Hyppönen shoe factory for a year.Making plans for his own factory

The completion of the second brick section of the factory was celebrated in the end of the 1930s; the old wood villa can still be seen on the background. Director Pentti Palmroth standing; the eighth person from the right. Photo: Kaarlo Luoto

In 1928, the making of shoes was started in the wood villa on the Partola Manor estate by Partolan Kenkätehdas Oy, founded by the 27-year old managing director. Pentti Palmroth considered the location of the factory excellent, because it was close to the city and, on the other hand, the Pirkkala municipality, where the factory was located, needed employers as agriculture could no longer sustain the entire population. He thought it was important that people did not need to give up their traditional living habitat. The rural surroundings offered the factory a peaceful workforce. The shoe factory was certainly welcomed in the municipality, where until now, the Pyhäjärvi sawmill had been the only significant employer. The State Aircraft Factory only started offering jobs to the locals starting from 1936.

Little by little, the shoe factory expanded. First, the villa was expanded by building a wooden addition, but in the 1930s, the wooden constructions made way to an extension constructed from red brick. Another four-storey T-wing was added crosswise and a third floor was added to the previous section as late as in the 1950s. The first cafeteria was situated in the drying barn cottage at the end of the factory, and it was then moved to the bottom floor of the brick building. Later it operated in the premises of Tisle Oy which had been built behind the shoe factory. This chemical factory was established in 1944.

Training and the employees

In the first years, the factory had 10–20 employees. In the beginning years, the skilled labourers mainly came from Tampere, but from the very beginning, the aim was to replace the professional workers with employees who had worked and trained themselves to the job at the family’s factory. The managing director was always of the opinion that any person aiming to be in a managerial position at the factory could not pick and choose when it came to work; everything needed to be learned personally on the job. Many workers started as apprentices. They were given trial tasks in a few departments of the factory, including design, cutting, stitching i.e., sewing, stretching, bottoming, finishing and packing. When the newcomers seemed to have a talent for something, they could start their training. Little by little, the profession was learned, and the apprentices could assume work with more responsibility, and among them, the factory later found its master craftsmen for the different departments. The goal was that each worker would feel they were valued for their work.

Also the managing director’s sister Kirsti started work in the factory after completing her middle school. First she was in the office working out payrolls and receiving orders. She remembers how crowded and elementary everything was in the wood villa when the director, office manager Ilmari Lehmus and she all worked together in the small room. The managing director’s desk had been built from wooden crates, but Lehmus, on the other hand, had a real desk which was on loan. As an apprentice she got to know the operation of every department and she was not allowed to skip any duties. She started taking an interest in designing models and studied the profession at home during the evenings with the assistance of the masters. The factory had two masters at the time and they had two apprentices. There were no women involved in shoe design at the time. She left her studies at the commercial college and her excitement in the industry took her to Germany to study shoe-making. After a year, she returned to Partola as a designer in the model department. Kirsti married in 1940, then moved to Kuorevesi as Mrs Karhumäki, and was no longer involved in shoe-making. She still remembers the incredible team spirit at the factory and says: “We were always talking about shoes and their marketing, even in the evenings when I popped in to see my brother.”

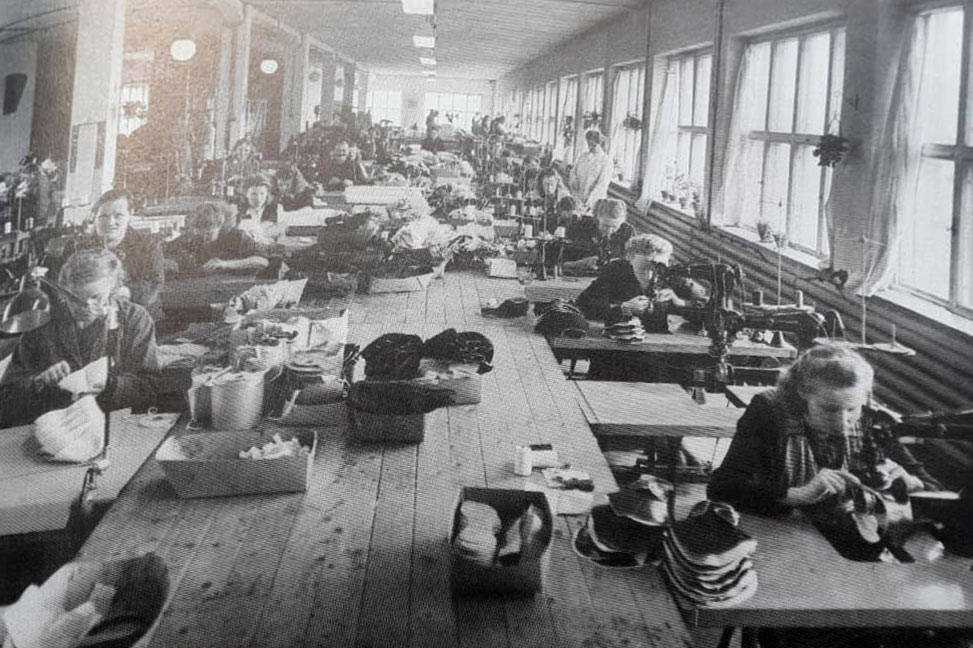

The sewing department under the direction of forewoman Laura Nurmi. Photo: Pertti Palmroth

Kaarlo Luoto started as an apprentice in the factory in 1936 when he was 14 years old, and worked in the stretching department. The department worked in contouring the shoe on the boot-tree after the cutting and stitching phases. When the factory got a new shoe-stretching machine, the director said: “If you can make the machine run, the job is yours.” The machine did start, and that’s how Kaarlo became a stretcher. In 1946, however, he had to switch jobs when the young couple could not find an apartment in Pirkkala. After three years, the managing director wrote a written request and was able to make Kaarlo Luoto return to Partola to head the stretching department as its foreman, as there was an apartment available for them. Although he only stayed for a year in his position, as some dispute lead to him resigning.

But he is still of the opinion, that the director was fair. For example, the director had given 500 marks of extra spending money to him and a few other recruits leaving to fight in the war. Regardless of the disputes, Palmroth also never protested in any way, and their relationship remained good. Another employee, Siiri Linden, says that she arrived at the factory at 15 years of age in 1937. She first worked in the sewing department for a few years, and then in the stretching department since the beginning of the 1940s. During the war, the factory manufactured military boots and cartridge bags. Siiri Lindell stayed in Partola until 1961. She remembers her employer in a positive way: “The honorary counsellor was always friendly and just.”

In November 1936, 15-year old Elli Toiva from Pirkkala’s Kranaatinmäki, started work in the sewing department. Going to work and then returning home again was difficult at times. The buses were full and their timetables were not suited for her work schedule. She remembers her first pay, 104 marks, and she thought at the time that it was an “awfully large sum of money”. Soon she bought a bicycle on account from Voi, and was happy to ride to work even late in the autumn. Elli Toiva remembers from the war time that everyone had a bag made of white fabric and filled with coal in case of gas being used in the war. For a week, everyone tried to work only at night, but it was too strenuous and it was stopped.

Elli Toiva was later able to move from office work to tasks involving machinery, and after studying the more demanding work phases, she ended up as a decorative stitcher. She stayed in Partola until the end of January 1984. When talking about the director, she says that he was pleasant and a good man, who had the habit of sometimes giving gifts. She also once received 500 marks which she kept between the pages of a book for a long time. Elli Toiva felt that the team spirit at the factory as always good.

Daily work at the factory

In the beginning, work days were from 7 am to 4 pm, and Saturdays from 7 am to 2 pm, with an hour for lunch. Later the work days fluctuated in length, and lunch hour was shortened to just 30 minutes. Making shoes was almost entirely done on piece wages, with only finishing and packing being paid as hourly work. At maximum, there were almost 200 employees working in the Partola factory.

Previously, there were free Saturdays on occasion in the summer, but it became a regular day off in the end of the 1960s. For the summer holiday, the entire factory stopped for the same time period. However, sometimes it happened that a certain summer shoe became so popular that holidays were postponed, so that orders could be filled and there would be enough pairs to sell.

“Ferris wheel”, clamping of the glue and the drying carousel. Photo: Pertti Palmroth

The director taught the people to be punctual. “He was precise as a clock,” says Pirkko Mattila, an errand girl who started work in the factory office in 1954 when she was 14 years old. In time, she started operating the switchboard, was then promoted to domestic invoicing and then served in payroll computation for the period 1972–1980. She is thankful when she thinks about her former employer who entrusted a girl with just an elementary school education with such demanding work tasks, and continues: “The counsellor would usually arrive at the factory at 8 am and then made regular rounds in the factory area. The workers knew when the director was coming. When the clock sounded for lunch hour, the lift came up and the director left for Partolanniemi. Excluding a few odd times, he usually returned at 1 pm: and went again on rounds. After work, he wanted a report booklet on his desk every day in order to examine the factory’s production numbers by department. In the beginning of the 1960s, production rate was approximately 500–600 pairs a day.”

Being polite was very important for him. He thought that the telephone switchboard was the gate to the factory, so he taught his switchboard operator how to handle her tasks. Her speech needed to be clear and understandable, her performance polite and energetic, and her voice joyful. Kaarlo Luoto also remembers the director’s advice on never protesting to a customer in any situation: “Showing a sour face was not allowed, no matter how wrong the customer was." Marjatta Salomaa says that her brother Pentti never criticised an employee in front of the others; he always discussed the situation with the foreman and handled issues in a subtle way.

The managing director also paid attention to the workplace wellbeing of his workers. The factory halls were bright, and Pirkko Mattila remembers how in her time curtains were purchased for the windows and indoor plants in the halls. At least in the departments where there were no large pieces of machinery. Employees were able to enjoy music four times a day, twice in the morning and twice in the afternoon. The women at the office took care of playing records according to a schedule, usually three records at a time, some marches and dance music. On the door leading from the sewing room to the office, there was a humorous and calming text with the words: “Don’t get nervous, just marvel.”

The boys follow in their father’s footsteps

Juhani and Pertti, the sons of Alli and Pentti Palmroth, used to work in the factory in various odd jobs in different departments during their secondary school times, especially during the summers. All work phases needed to be learned. Their father demanded of them what he demanded of everyone else, you could not be late. After secondary school, the boys went to study abroad. At first they studied the shoe industry in England for three years and completed their engineering studies at a technical institution. Then they spent a year in Germany.

After returning home in 1952, the boys naturally started working in the factory. Juhani took his time getting to know the operation of each department, and then settled to work in the office. Pertti instead was interested in design, models, colours and sales. The products were mainly women’s fashion shoes and boots. For example, in autumn 1952 he designed a Miss Universe collection for Armi Kuusela. He also toured around Finland selling products, and trade fairs were also held in Helsinki in Hotel Kämp. During other times, he handled sales and purchasing at the factory. Father Palmroth was managing director until his death in 1968.

The good reputation spreads and export is booming

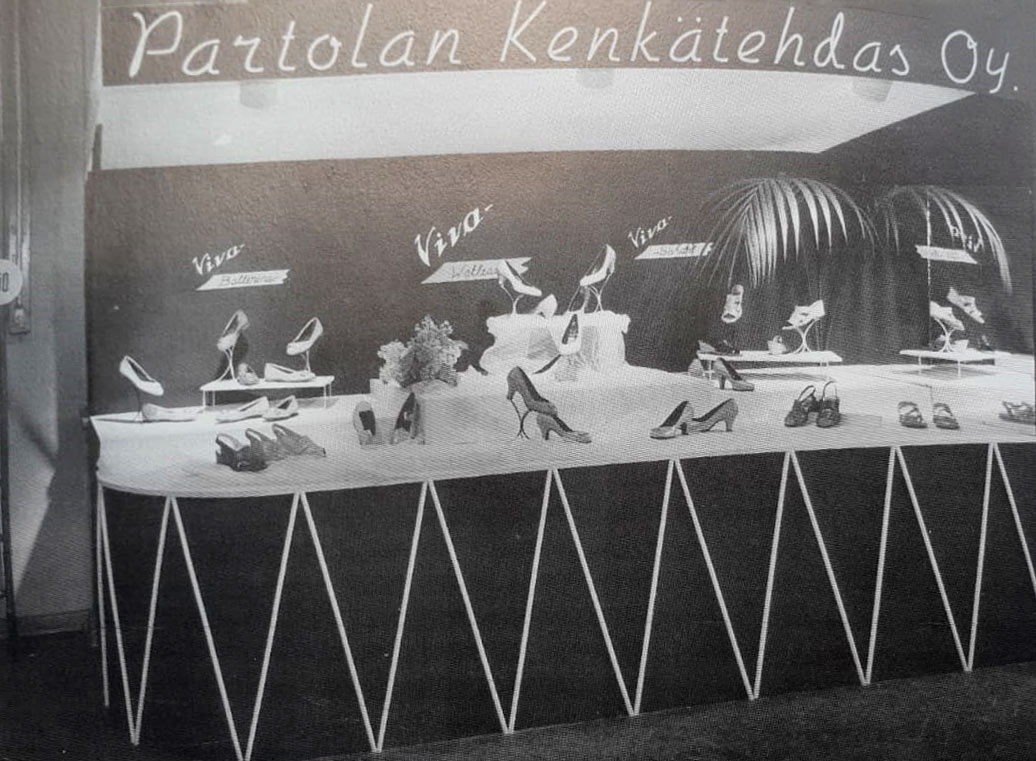

Already in 1935, the Partolan Kenkätehdas shoe factory’s Viva collection raised a lot of interest in a trade fair organised in the Helsinki Fair Centre where the Viva shoe was awarded with a gold medal. Kirsti Karhumäki remembers an occasion when our very own Miss Europe, Ester Toivonen, visited the same fair and ordered many pairs of Partola shoes. One reason for this could have been that she had acted in the same film with the factory’s travelling salesman, Toivo Palmroth, who was the siblings’ cousin.

The first exhibition at the Tampere trade fair in the lyceum hall in 1953. Photo: Pertti Palmroth

The Viva shoe was advertised in the newspapers in its day, for example, as follows: “Why travel far, when you can get Viva shoes nearby.” “Beautiful, durable and pleasant to wear, such is the Viva.”

Kirsti Karhumäki says that she was amused at how her brother could be egged on, for a sum of money of course, to market the red Viva shoes by wearing them to walk along the street Hämeenkatu, from end to end and back again, which was a popular activity amongst the young people in Tampere. She also remembers organising shoes for the models, among them the then top model Nora Mäkinen, to wear in a fashion show in Hotel Tammer.

Production expanded further in 1960 when the Palmroths acquired the Hämeen Kenkätehdas shoe factory in Tampere. Export abroad also started booming around the same time. In addition, in 1966 Palmroth Holland N.V. was founded in the Netherlands.

In the 1930s, caretaker Otto Nieminen had transported shoe boxes to the station by horse and later by lorry, but in the 1960s, it was time for trailer lorries. These vehicles rolling up in the factory yard made curious pairs of eyes appear in the windows of both the factory halls as well as the office. It has remained with Pirkko Mattila how at least once, the honorary municipal counsellor himself was hard at work in the shipping room, and even went inside a trailer lorry to monitor that order was maintained among the shoe parcels. After all, it was a larger shipment than usual.

Daily production in the 1970s was approximately 1,200 pairs, of which 60% was exported. Exporting was experiencing a strong boom. Design Palmroth products acquired great success in many Western countries due to their original design and the work methods the company had developed. Palmroth shoes ended up as the shoes for various work uniforms, and they were showcased in international fashion magazines. The Partolan Kenkätehdas shoe factory has received acknowledgement for its distinguished export operations and its unique design; among others, the Junior Chamber International has granted Partola an export prize in 1966, and a French Good Taste prize was received in 1965.

Attending to civic duties

The managing director’s interest was directed at industry, and especially the development of the shoe sector. He took an active part in his own sector’s association activities and was a board member in the Kenkätehtaitten Keskusliitto (the central association of shoe factories) from 1944 and its Chairman from 1963. In 1940–1945, he had notable posts in the service of the Ministry of Supply and the Military Economy Department of the Finnish Supreme Headquarters.

Swimming lessons on the Partola beach in the summer of 1939. Photo: Ritva Pere

Pentti Palmroth felt that it was good to have a fruitful interaction between the municipality and industry. In this respect, his activities were exemplary, as he participated in in the conduct of public affairs in the municipality of Pirkkala, in the church parish and in many associations for approximately 40 years. For his achievements in municipal civic activities he was granted the honorary title of municipal counsellor in 1951. Apart from improving his own municipality, the improvement of the entire Pirkanmaa area, the Tampere region, was close to his heart His investment in these activities was quite significant for decades. At his time, Juhani Palmroth walked in his father’s footsteps also in this area and held positions of trust in the 1960s and 1970s tending to municipal matters and resolving even wider issues.

The managing director’s old time factory owner spirit

Pentti Palmroth did not care for his workers’ trade union activities, because he thought he was doing a good job taking care of his employees’ income and other wellbeing, and also that of their families.

The managing director gave thanks to the workers by arranging an annual Christmas party for all the families. The factory representatives presented a review of the past year, and then there was food and beverages. The workers arranged the entertainment. There had to be playful competitions, and, of course, the prize was a pair of the factory’s boots. In addition to this, the managing director also arranged other leisure time recreational activities. In the winter time, there was ski competitions with their own categories for adults and children. The factory workers also participated in ski competitions between factories. In the summer time, recreation mainly consisted of various ball games. The first swimming schools in Pirkkala were even arranged at the Partola beach by the Finnish Red Cross, at the initiative of Pentti Palmroth. Someone has playfully stated that he was the first youth instructor in the municipality.

The managing director used to stop by at his tenants’ apartments to see that their affairs were in order or just to have a visit and chat with his workers. On his Sunday walks he could get carried away and throw some darts with the boys in Pikku-Pispala.

Times of change

Honorary counsellor Pentti Palmroth died unexpectedly in the autumn of 1968 at the age of just 67. After this, his sons took care of the factories together for a while, but they were then divided such that Juhani Palmroth took on the Partolan Kenkätehdas shoe factory, and Pertti Palmroth took on the Hämeen Kenkätehdas shoe factory, later called Hamken Oy.

The Partolan Kenkätehdas shoe factory continued its operations under the leadership of Juhani Palmroth up to the end of 1978 when he suddenly passed away. This created a new and confusing situation which was most likely not easy to cope with. The factory continued its production reasonably well, partly due to the heirs and partly to external leadership until 1986 when the factory’s operations ended.

Hamken Oy, previously Hämeen Kenkätehdas, continued operations under the ownership of Pertti Palmroth in the Sarankulma area in Tampere where the factory received a 500-square-metre extension in 1996. Hamken Oy manufactures 900–1,000 pairs of shoes each day and also approximately 25 000 bags each year. In 1995, the company purchased an industrial property in Pirkkala which manufactures soles, and also the Waterproof line shoes since 1997. This creates a partial return of the Palmroth shoe manufacturing tradition in the Pirkkala municipality after about 10 years.

Sources:

The article is from a book called ‘Pitkin poikin Pirkkalaa: Pitäjälukemisto’

Written by Raili Taberman

Published 1997

Aamulehti 25.9.1968

Miettinen, Ahti, Kuinka kenkätehdas syntyy ja kasvaa. Tammerkoski 1960.

Interviews with Kirsti Karhumäki, Erkki Leppänen, Siiri Lindell, Kaarlo Luoto, Pirkko Mattila, Pertti Palmroth, Seppo Palmroth, Marjatta Salomaa, and Elli Toiva